Weekly doom round up

26 January 2026

Each week I’ll try to get a round-up of some of the pieces I’ve been reading over the past week that shape my understanding of the transition (for better or worse). I’m trying to keep it to 4-5 max - if there’s something I should have read lmk!

Oil’s not well

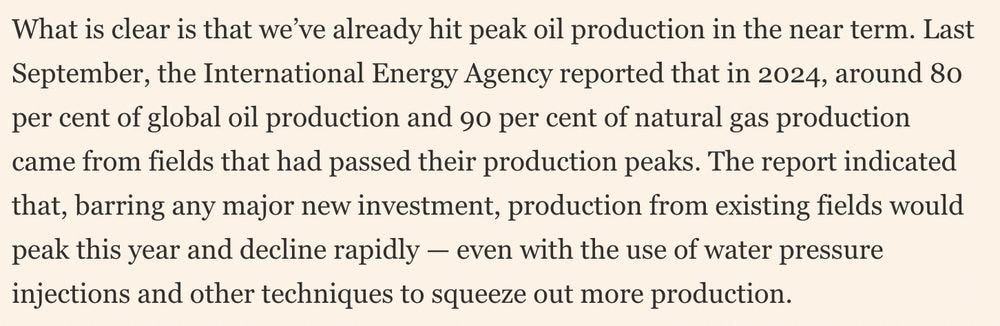

Is peak oil back? Peak oil doesn’t mean ‘oil running out’ and never did. The argument was oil production had reached the limits of growth. It contended that after the peak of production, there would be a decline in output and this would have a range of chaotic and destructive impacts. At its most extreme, it was a political-economy based not on labour or capital but energy. We’ve since seen an inversion of the idea with peak demand being touted as here or soon to be here for fossil fuels.

But at the margins, peak oil from a ‘supply side perspective’ never went away. It’s even become the analytical basis for investment houses such as Goehring & Rozencwajg. Economics from the top down has a great run down of lessons to be learnt (and not learnt) from the body of what we should call peak theory. But the link I wanted to post today was one from the Financial Times – The Great Oil Head Fake. Why? Because peak oils back in the mainstream after almost 2 decades in the cold.

Build it and they will come?

Sticking with oil and gas, Data Desk have done a deep dive into LPG, essentially arguing that much of the predicted demand is (a) materially unable to be realised because of limited construction and infrastructural capacity and, more importantly, (b) performative:

Industry players’ demand forecasts contain an element of being literally performative. That is, those divining the future numbers are in doing so aiming to create expectations that make their desired futures more likely. In the face of uncertainty about from where — and whether — demand will emerge, the manufacturing of demand is rife in the region, as players with skin in the game try to lock in greater volumes.

Much as with Trump’s attempt to bully industry into investing in Venezuela, or to get Europe to buy gas, the fossil industry increasingly looks like it’s trying to manifest a future on vibes alone.

Refugees aren’t getting any of the (carbon) credit

At risk of self-promotion, David Harvie and I published an article with the Jacobin on how the UNHCR is trying to solve its deepening financial crisis by putting refugees to work making carbon credits. It’s based on a longer academic piece in Race & Class. It’s worth reading (as long as you are prepared to be depressed) with this FT Big Read on the UN’s crisis, and the unravelling of the inadequate refugee and aid regimes created piecemeal after WWII.

As displacement intensifies (and already is), it’s hard not to see the weaponisation of migration, and the paramilitarisation of border policing, as the only climate adaptation the West is whole heartedly invested in.

Banking on finance?

Is this good news? If so, it’s not a lot of good news, and definitely not deliberate.

For years, climate experts have insisted that markets will naturally push companies to take climate change more seriously as risks become more apparent. Fresh research indicates that borrowers are starting to face a financial penalty for ignoring the dangers ahead. This month, a paper published by the European Central Bank found that banks with the greatest so-called transition risks now “face significantly higher borrowing costs” in funding markets. That followed a December paper by analysts at the Central Bank of Ireland, which showed that companies facing physical climate risks are in a similar predicament, and will need to provide more collateral.

The Great Drying Out

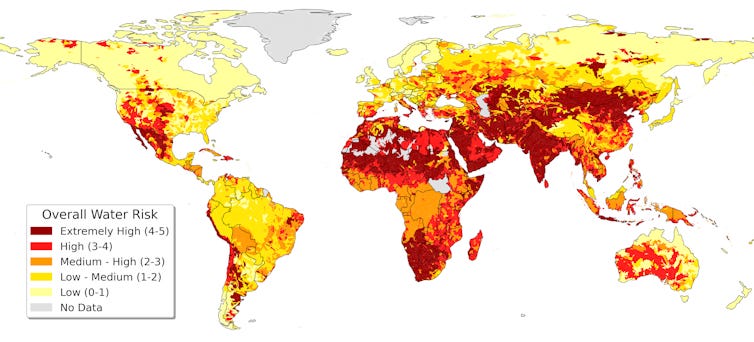

We are entering into a world of water bankruptcy. This story got some circulation, but in amongst the raw brutality and chaos of Trump’s version of libertarian authoritarianism you might have missed it. Tl;dr:

Water bankruptcy is a chronic condition that develops when a place uses more water than nature can reliably replace, and when the damage to the natural assets that store and filter that water, such as aquifers and wetlands, becomes hard to reverse.

4 billion people – nearly half the global population – live with severe water scarcity for at least one month a year

3 billion people and more than half of global food production are concentrated in areas where water storage is already declining or unstable. More than 650,000 square miles (1.7 million square kilometers) of irrigated cropland are under high or very high water stress.

Over 1.8 billion people – nearly 1 in 4 humans – dealt with drought conditions at various times from 2022 to 2023.

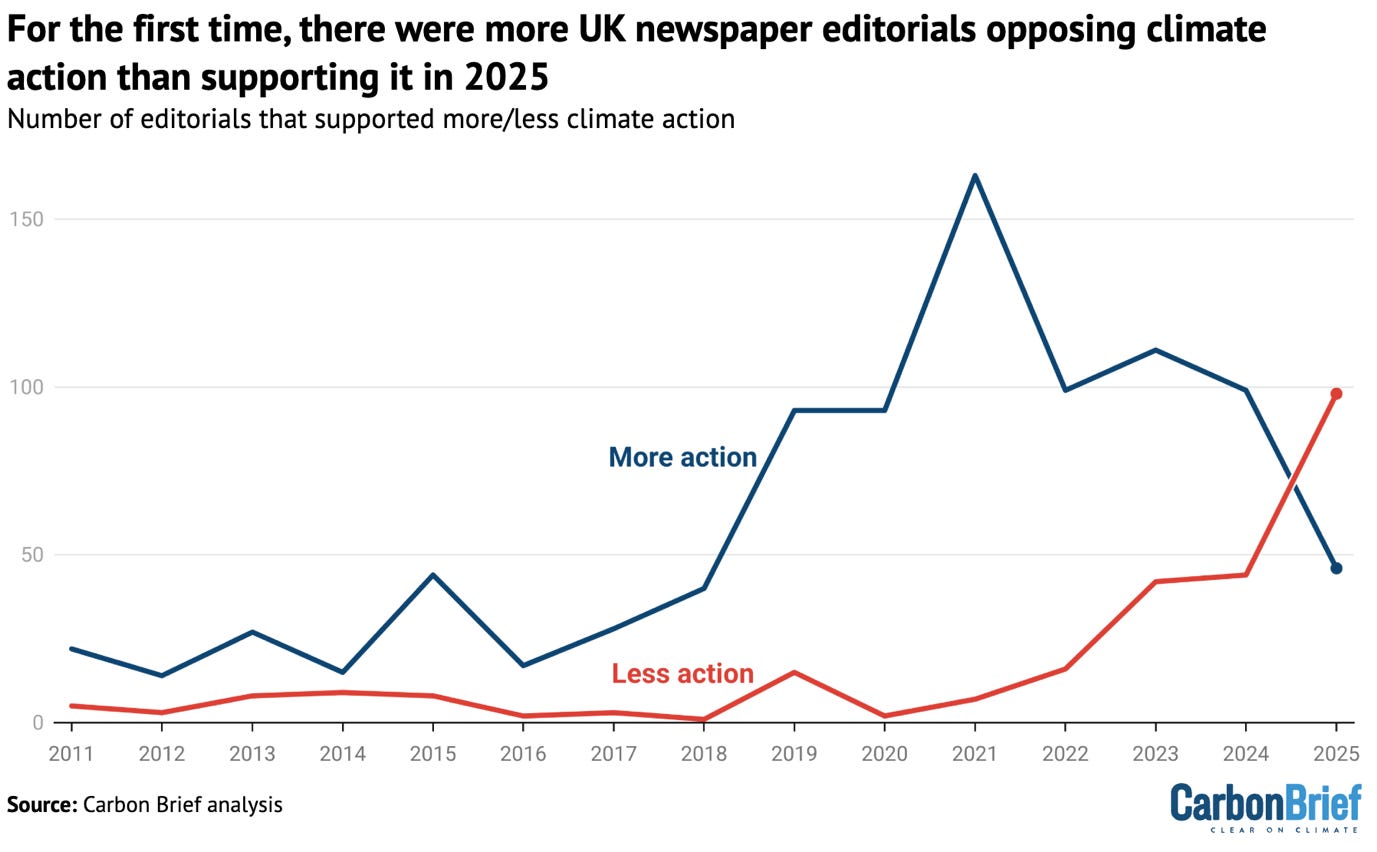

The anti-climate agenda

If shadow banning and algorithmic distortion weren’t enough, climate disinformation is increasingly baked into the news. I’m not talking about the measly mouthed genocide denying BBC, but the fact that more UK newspapers now oppose climate action than support it.

Given how over half of people – and over 80% of Gen Z – get their news from social media, as concerning is the increasing use of AI to generate disinformation and the clear right wing climate denialism built into X’s Grok.